The Classic Era – 1958-79

| It’s 1958, lightweight racing bikes are showing signs as possibly growing as a business. Unfortunately, the Paramount program had suffered from a lack of attention. The few frames being built were built at the Wastyn shop on the west side of Chicago. Aside from an occasional use of Nervex lugs, the designs, methods and tooling were the same as had been used in the 1930’s.

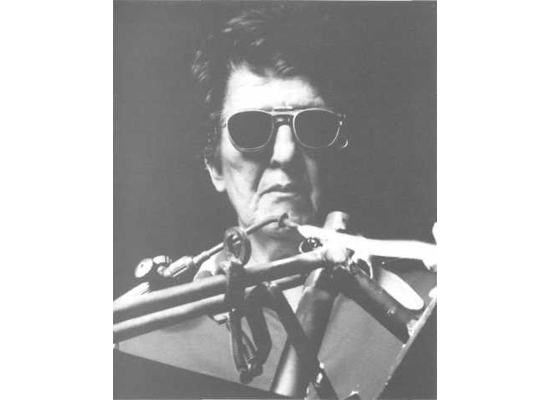

Frank Schwinn finally got fed up with the situation and put Keith Kingbay in charge of the Paramount. Kieth was already in charge of Schwinn’s Parts Department. Keith grew up Kenosha, Wisconsin, and raced during what was a pretty hot scene in the 40’s before moving to Chicago to work for Schwinn. Keith selected a couple of other bike racers, Frank Greco, Joe Magnani and Frank Brilando as well as engineer Spike Shannon to rejuvenate the program. Keith’s war cry was, “I don’t want the Wastyns to be able to say they have anything to do with the Paramount anymore.” |

Frank Greco, a Chicago native, spent his war years in California, and stayed out in California after the war. During that time he started the San Diego Cycle Club, bought his first Paramount and became very successful at selling them. Around the time of the Korean War Frank moved back to Chicago to join Schwinn, first in the assembly department and them in the Parts Department. He also helped Ovie file frames when at the factory and, along with Stan Natanek, assembled Paramounts.

Joe Magnani, though a US citizen, raced the European circuit before World War II, marrying a French girl just before hostilities began. He ended up trapped in France during the War, where he helped with the resistance movement. He joined Schwinn after the end of the War.

Frank Brilando, engineer, earned spots on the 1948 and 1952 US Olympic teams, joined Schwinn in the early 50’s. Frank went on to head Schwinn’s Engineering through the 1960’s to the 1980’s. Spike Shannon, a race enthusiast and bike designer, was responsible for the frame layouts.

In 1957, Frank was put in charge of building the Paramounts from scratch. He worked with Frank Brilando to develop processes for using silver solder instead of brass as the brazing material of choice. Silver solder meant a real revolution in frame building since it allowed brazers to use much lower temperatures than they needed for brass brazing. This kept more of the basic strength in the tubing and prevented other mishaps. It also simplified cleanup.

Greco worked feverishly for six months, learning everything he could how to build racing bicycles including fixtures, alignment and geometries. It was particularly tough because he couldn’t take advantage of any of the old sources of framebuilding know-how. Schwinn’s updated Paramounts now all sported Reynolds 531 double-butted tubing, Nervex lugsets and bottom bracket shells as well as Campagnolo dropouts. Up until then, only a few of the Paramounts had this level of equipment. To make production even more special, Schwinn cleared off an area right next to the office entrance and fenced off the Paramount frame shop from the rest of Schwinn’s production. This area became known as “the Cage”.

Frank started production in 1959. Wanda Omelian performed brazing almost from the outset, and Stanley Peters joined the group in 1960 to file. Joe Magnani developed the component side of the Paramount, working on race wheel building, Campagnolo derailleur systems and other top of the line equipment. Joe had quite a glorious history in racing including a stint in Europe before World War II. The Paramounts received the best of everything, including hand sprayed paint and the delicate pinstriping of Frank’s father, Joe Brilando and Adam Smith.

Though the Wastyns were shut out out Paramount production, they remained Schwinn dealers under favorable terms with Schwinn. Oscar Wastyn Sr. had been nearing retirement. Though the Wastyns no longer build Paramounts, many of their later frames were painted at Schwinn.

Along with the new technology, Schwinn updated the styling. Gone were the pre-war stylings. The first of the new decal sets combined the new Schwinn “spaghetti”-style font with the popular “Disneyland” gothic theme and a completely redesigned seat panel.

The updated Paramount turned out a success. Production, which before amounted to fifty to one hundred frames per year, grew to several hundred per year by the mid-60’s. By then, Frank Greco began to expand staff to include Lucille Redman who, along with Wanda, had become so closely identified with the Paramounts by the mid-70’s.

During 1963, Schwinn began the transition to the classic “starburst” decal shown on the “vintage” decal set. In ’68, Schwinn updated the seatmast panel to reflect Schwinn’s name change to Schwinn Bicycle Company from the original Arnold Schwinn and Company. As a sidenote – Arnold was the name of the financial backer behind Schwinn at the company’s founding in 1895.

It includes the later “Olympic Rings” seat mast panel and the “TI” (Tubes Investments) version of the Reynolds 531 tubing sticker.

During the 60’s, Schwinn began chroming the dropout and fork tips of all road Paramounts. For an extra charge, riders could order a fully chrome plated Paramount. Plating wasn’t favored by the racers since plated bikes weighed more than painted bikes. Below are two shots of the classic Nervex Professional lugset:

Parts supply was always a challenge. The Nervex Professional lugset, a stamped lug with its well-known and ornate profile, required considerable work in order to make a good frame. In addition, the bottom bracket was poorly machined. Someone in the 50’s had purchased a huge supply of bottom bracket shells that took better than a decade to finally use up.

By the end of the 60’s, resentment inside the factory over these lugs and shells was so high that when the supply finally ran out in the late 60’s, Schwinn sourced the Prugnat lugs as a substitute. The builders loved it, but the move was not popular among dealers and riders, since most people favored the carefully filed and beautifully ornate Nervex lugs. Schwinn compromised by keeping the Prugnat bottom bracket shell while returning to the Nervex lugset.

Paramounts grew its model offerings:

P-10 – Deluxe Paramount – designed for non-competition road riding and included front and rear eyelets, 27 x 1 1/4″ clincher tires and Weinmann center pull brakes. It usually came with Campagnolo Record components. You could order it with Campy side pulls and/or custom geometry as an option.

P-11 – Paramount Tourist – designed for upright bars and recreational rides. It was available on a special order basis only. The ladies version was designated P61.

P-12 – This was the old designator for the Paramount Racer – now becoming the P10.

P-13 – Road Racing Paramount – designed for competition, this model came with tubulars and Campy sidepulls stock.

P-14 – Track – Full Campy track components including wide flange hubs and tubular tired wheels.

P-15 – Deluxe Paramount with 15 speeds (triple front chainrings). Start with the P-10 and add a wide gear range (generally a Shimano or Huret) long cage derailleur.

Starting in 1971, Schwinn outsourced excess Paramount production to Pioneer Manufacturing of Racine, Wisconsin, owned by Don Mainland. Don was an accomplished bike racer as well as successful industrialist. After racing in the midwest, he raced in Japan’s Kierin circuit in the early 50’s. He then returned to the US, where he set the coast to coast cross country record, which stood for eleven years. Don’s firm supplied the 1972 Olympic frames and Schwinn Superiors during the 1980’s. His tooling firm supplied Schwinn’s manufacturing all the way until 1990 in Mississippi.

You could customize your Paramount in a variety of ways, including custom gerometry. Riders started asking for split cable stops and downtube shifter bosses.

By ’74 or ’75, the Paramounts also became available with a so-called “short coupled” design. This design featured a seatmast which curved around the rear wheel, allowing a shorter wheelbase. It was offered to touring riders as a way to improve climbing by shifting the weight distribution rearward, as shown below:

As the 70’s progressed, Schwinn moved away from the classic seatmast panel to a cleaner look with two sets of World Championship stripes. Schwinn also moved from the vintage typeface to the 70’s “block” style typeface:

During the late 70’s Schwinn also issued special “team” decals for their sponsored teams, most importantly the Schwinn Wolverine Team under legendary coach Mike Walden:

During the 70’s, Paramount sales rose to 1,200 units annually. Schwinn supplemented Paramount production with contract-built frames by Don Mainland and Roger Nelson. Don and Roger, both riders from the 40’s and 50’s, had built up a successful tooling business in Racine, Wisconsin. He already supplied tooling to Schwinn. At Paramount’s peak in the mid-70’s, 10 frames per week came from Wisconsin and 15 from Chicago. There is no obvious way to distinguish the Wisconsin-built Paramounts from those built at the Schwinn factory. Serial numbers were issued after the bikes were built.

The 70’s also marked a time of considerable change in the high-end bicycle market. Except for Paramount, US framebuilders had pretty much died out up through the 50’s and 60’s. In the 70’s, a new generation of builder appeared on the scene. On the East Coast, builders like Tom Kellogg and Ben Serotta got their start. Both of these builders made bikes for Schwinn’s competitors like Ross and Huffy. In the Midwest, a number of small builders started up including Matt Assenmacher, Terry Osell, Tim Paterak and a young man from the western suburbs, Marc Muller. The West Coast had its own cast of characters, including Tom Ritchey and Eisentraut.

Several of these builders had visited and for short periods of time had apprenticed in the Paramount cage in Chicago.

Materials and technology had also undergone substantial change in the 1970’s. Reynolds 531 the undisputed leader in butted tubing, faced challenges from many corners: The Italian firm Columbus made a major push, as did the Japanese firm Tange.

Reynolds introduced the heat-treated version of their 531 tubeset – 753 – in 1977. With 753, Reynolds added several requirements for builders to use 753: Most importantly, any builder who wanted to use 753 had to certify with Reynolds. In addition, Reynolds placed several other restrictions on the brazing of 753 including tight temperature limits and a prohibition against chrome plating. 753 was offered in unprecedented wall thicknesses – a .4 mm wall for both top and downtubes. This allowed lighter bikes to be built than had ever been allowed in the past.

Lug making in the 70’s had undergone a similar revolution with the introduction of investment casting technology. Investment castings are so precise that they drastically reduce the amount of filing and polishing required to complete a bike. Moreover, the casting can be designed to support a fully mitered tube all the way to where it meets the adjoining tube. This allows a smaller lug to be built that provides better structural support than a larger lug without the full tubing support. Investment castings lacked the ornate look of the Nervex lugs but they were cleaner and lighter.

Components from Campagnolo continued to advance, but a more radical revolution was taking place in tire technology from Europe with the introduction of 700 x 18C and 700 x 20C tires. These tires didn’t have offer the durability and comfort of 27 x 1 1/4″ tires, but for all out racing they offered a significant weight advantages where weight savings count the most.

Geometry also went through changes in the 70’s with shorter wheelbases, steeper head angles and steeper seat angles replacing the established geometries of the 60’s. These became fashionable for criteriums – the fastest growing type of race in the US.

All during the 70’s, the Paramount continued to sell in its well-proven design. The customer base for the bike changed, however, from primarily bike racers to older, wealthier riders looking for their ultimate cycling reward. By 1979, the Paramount had been passed, technologically, by a whole generation of American as well as foreign builders.

While the Paramount had proven itself the most successful American racing bike of the 20th century, it became apparent that changes needed to take place or its reputation would be lost.