Arnold, Schwinn & Co. was principally a builder of racing and other adult bicycles since its founding in the 1890’s. Up until the early 1930’s, Schwinn was not a brand name to the public. Schwinn’s own production was sold under the World, New World, Excelsior or Henderson brand names. Schwinn also produced a number or private label bikes, such as the Ranger during this period.

When Frank W. Schwinn took charge of the company after the start of the Great Depression, he introduced Schwinn as a brand name tied to a line of well styled balloon tired bicycles. This became such a hit that it dwarfed Schwinn’s traditional mix of racing and racing-like adult bicycles.

As Schwinn built its name on its mass-produced balloon-tire bicycles in the 1930s, many people lost the connection with its racing heritage even though Schwinn continued to sponsor bicycle racing. Frank W. Schwinn saw potential, both commercial and promotional, in offering an exclusive brand of hand-built race bicycles that he named Paramount. It was the spearhead of a larger effort to build an adult bicycle market in the United States.

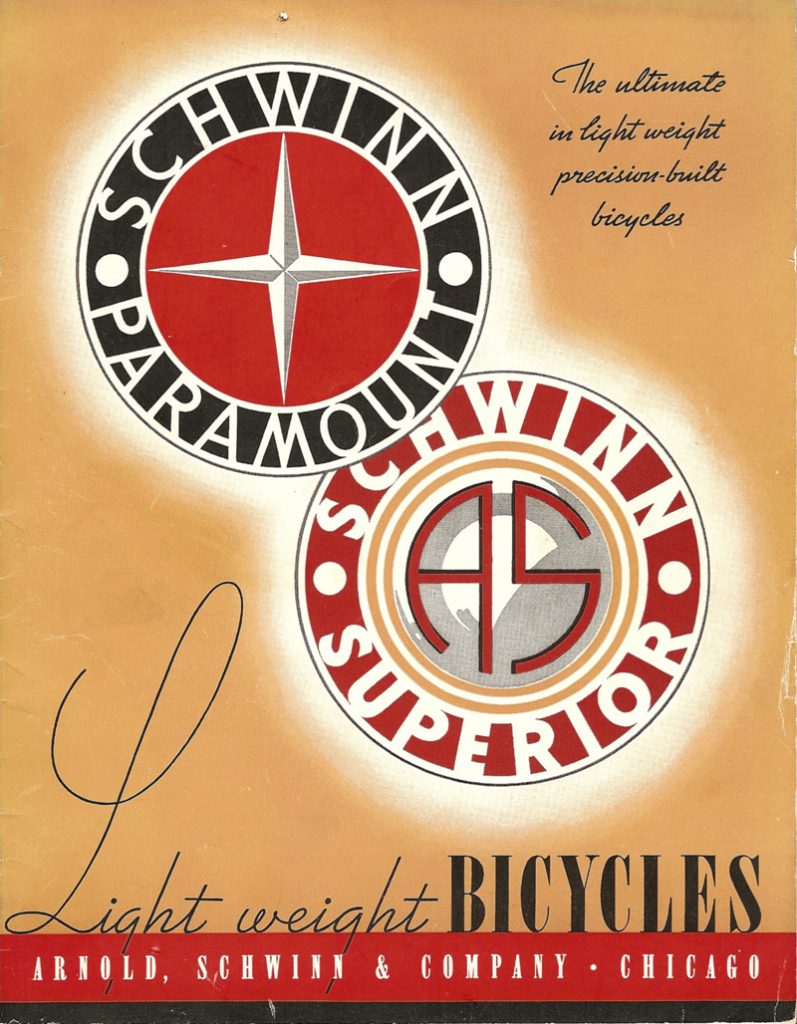

In 1938, Frank W. Schwinn officially introduced the Paramount. In its introductory catalog, Schwinn dedicated the Paramount brand to the production of world competitive bicycles.

High strength steel alloys were just becoming available as bicycle tubing and Paramounts from the outset were made with the new Chrome-Molybdenum formulas using brass lug-brazed construction. The lugs were carefully carved to improve strength and achieve a clean look.

Though Paramount’s official introduction took place in 1938, the origins of the bike started earlier in the decade when Emil Wastyn became the framebuilder of choice for Schwinn’s professional six-day racing team. Emil ran a bicycle store and frame shop not far from the Schwinn factory on Chicago’s West Side. He had built an impressive reputation as a framebuilder since he arrived in America in the first decade of after the turn of the century. Though no longer building frames, the Wastyn shop still operates and includes a museum showing the work of Emil and his son Oscar. Click here to visit their web site.

Paramount-labeled bikes began to appear late in 1937, especially for Schwinn’s key six-day riders. In fact, the initial catalogs included letters from the current stars which promoted Emil Wastyn as much as Paramount.

During the next twenty years, most of the Paramounts would be built at Wastyn’s shop. The earliest Paramounts followed Emil Wastyn’s signature styling (balled-end seat stays, for example) and keyhole-styled lugs. Over the years from 1939 to 1941, Paramounts evolved to have their own specific style – particularly the famous slant trimmed seat stays which remained in effect for 50 years. Emil and his son Oscar built all the Paramounts from 1938 to 1941.

Schwinn also produced a variety of machined components to complement the frame – particularly a set of beautifully crafted wide-flange hubs. Schwinn also made parts such as stems, handlebars and even pedals, each marked with the famous Schwinn name in script.

Production halted during World War II. When Paramounts started back up after the war, Emil was entering retirement and his son Oscar continued building frames, both under the Wastyn and Paramount names.

After the war, demand for racing bikes (as well as interest in racing) fell dramatically. Schwinn attempted to bring production back in-house, hiring a builder named Ovie Jensen. Ovie was a capable builder but was devastated by the tragic death of his daughter. After problems were discovered with some of his ’56 Olympic team bikes he was moved back to Wastyn’s shop. Even then he had remained too despondent to be effective and he was eventually moved out of Paramount production altogether.

During the 50’s, Schwinn started feeling the influence of a number of bike racers including Kieth Kingbay, bike racer and engineer Frank Brilando, Joe Magnani, Spike Shannon and Frank Greco, to name just a few.

In the broader scope of Schwinn’s business during the 1950’s, Paramount was but a stepchild. Bike racing, a major professional sport in the 1930’s, had all but died by the 1950’s. The adult bike business failed to materialize. So Paramount was shifted to the Parts division, under Kieth Kingbay.

Kieth was an ex-bike racer from Kenosha, Wisconsin. He became the point man for Schwinn’s support of bike racing and then was put in charge of Schwinn’s Parts Division in 1956, a group that provided aftermarket parts to Schwinn’s dealers and distributors. The Parts Division was hidden away in Excelsior building (the old motorcycle factory), half a mile away from the main Schwinn complex. There, he could purchase componentry for special projects, like a new-technology Paramount with derailleurs and the new French Nervex lugs. Schwinn built its first derailleur bikes in the early 1950’s. It was a period of considerable experimentation.

Beginning in 1952, a few of the Paramounts were built with the new Nervex lugs, Campagnolo dropouts and, of course, the new-style shifting system, the derailleur. The Nervex lugs eliminated the hand carving required of the old BSA lugs used since the turn of the century.

During this period, Schwinn offered the following models (based on the ’56 catalog). Even through the ’56 catalog, the Paramounts were still advertised as having the keyhole lug design:

P11 – Tourist. This was the classic “English Racer”. It had keyhole lugs, Reynolds 531 tubing, plated chainguard, Paramount racing crank and hubs. A Sturmey-Archer three speed rear hub was also available as was the option of either a “matress” saddle or the venerable Brooks B-17. It came with extruded aluminum alloy rims and Schwinn Puff or Breeze (clincher) 26″ tires.

P12 – Racer (track bike). It came with full Paramount gear, alloy rims and tubular tires.

P-61 – Ladies model. This was the ladies version of the P11.

At one point Pete Gadron assembled Paramounts along with Joe Magnani in the so-called Continental room.

After Ovie’s departure, engineer George Flagle, built some bikes for about six months, but most of the production went back to the Wastyn shop.

Schwinn had made great strides in frame finishing during this period, decorating the Paramounts with the new metallic paints then becoming available. Joe Brilando, Frank’s brother, had developed extraordinary skills at the delicate art of pinstriping. Many of the Paramounts of the 50’s had intricate box striping in multiple colors.

Visionaries like Kingbay could see that adult bicycles could finally become a market. They felt, though, the Schwinn needed a take control of its top of the line Paramount, once and for all.